|

|

|

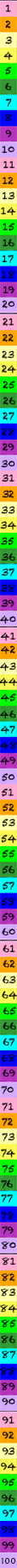

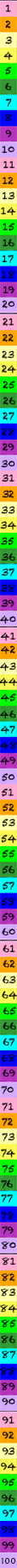

Menu 1 .55 Time :28

|

Menu 2 1.74 Time 1:27

|

| Total: 425,792 1,704 23:40 |

| Menu-Body 30%, 4% 1/3, 1/980 |

| Chapters 96 |

| Pages per chapter 17.75 14:48 |

Views

|

Visitors

|

|

1 Eratosthenes wrong 4 137 1:50

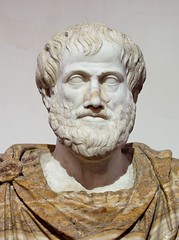

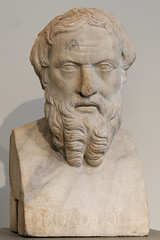

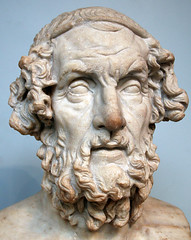

| 1. The science of Geography, which I now propose to investigate, is, I think, quite as much as any other science, a concern of the philosopher. In the first place, those who in earliest times ventured to treat the subject were philosophers — Homer, Anaximander of Miletus, and Hecataeus. Philosophers were also Democritus, Eudoxus, Dicaearchus, Ephorus, with several others of their times, and further, their successors — Eratosthenes, Polybius, and Poseidonius. Wide learning makes it possible to undertake geography, possessed solely by the man who has investigated things both human and divine. The utility of geography is manifold, concerning the activities of statesmen and commanders, knowledge of the heavens, and things on land and sea, animals, plants, fruits, and everything else seen in various regions. It presupposes in the geographer the philosopher, who busies himself with investigating the art of life, that is, of happiness. I must go back and consider each point in greater detail. First, Homer is the founder of the science of geography. He declared that the inhabited world is washed on all sides by Oceanus and mentioned some countries by name, leaving others to be inferred. Homer describes Ethiopia and Libya and the people living in the far east and west. He places the Elysian Plain in the west, where Menelaus will be sent by the gods, and describes the Islands of the Blest to the west of Maurusia. Homer also indicates that Oceanus surrounds the earth, describing the Ethiopians living at the ends of the earth and on the banks of Oceanus. |

|

| 2. In undertaking to write on a subject previously addressed by others, I should not be blamed unless my treatment is entirely repetitive. Despite excellent contributions by past geographers, much remains to be explored. If I can add even a little to their work, it justifies my efforts. The Roman and Parthian empires have expanded our geographic knowledge, much like Alexander's conquests did in earlier times, as noted by Eratosthenes. Alexander's campaigns opened up much of Asia and northern Europe to us, while the Romans have detailed western Europe and beyond the Ister River to the Tyras River. Mithridates and his generals extended our knowledge to regions near Lake Maeotis and Colchis, and the Parthians have illuminated Hyrcania, Bactriana, and the northern Scythians. Hence, I might have new insights to offer. My criticisms will mainly target successors of Eratosthenes, though contradicting such authoritative figures is challenging. If I criticize respected geographers like Eratosthenes, Hipparchus, Poseidonius, and Polybius, it’s with respect for their generally accurate work. Addressing Eratosthenes specifically, I will also consider objections raised by Hipparchus against him. While Eratosthenes, who studied under many eminent figures, might not be as unreliable as some suggest, his judgment in selecting philosophers to follow shows inconsistency. He studied under Zeno of Citium but ignored Zeno’s successors, favoring those who opposed Zeno and failed to establish lasting schools. This vacillation reflects his reluctance to fully commit to philosophy, evident in his various works. Nonetheless, I aim to correct his geographic errors wherever possible. |

|

| 3. Eratosthenes is wrong in giving undue attention to unreliable sources, like Damastes, despite occasionally acknowledging their inaccuracies. Even if parts of their accounts hold truth, they shouldn't be considered authoritative. Instead, credible figures, known for their accuracy and integrity, should be cited. Eratosthenes himself recounts a tale from Damastes, who claimed the Arabian Gulf was a lake and that Diotimus sailed an improbable route to Susa. Eratosthenes' critique of such stories is undermined by his own acceptance of dubious claims, like his assertion that the Gulf of Issus is the easternmost point of the Mediterranean, which contradicts his own measurements. Furthermore, Eratosthenes' approach is inconsistent. While he recognizes the limitations of ancient geographical knowledge, he still perpetuates certain myths. For example, he asserts that early Greeks only coasted for trade or piracy but later contradicts himself by claiming ancient mariners lacked the courage to venture into the Euxine Sea. Historical figures like Jason and Odysseus, however, are evidence of extensive ancient voyages. Eratosthenes also mishandles geographical phenomena, like the presence of shells far from the sea. He praises Strato's and Xanthus's theories about changing sea levels and continental shifts but offers no substantial critique. While Strato suggests varying sea depths cause these changes, the actual reasons involve geological activities like earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. Eratosthenes also fails to grasp the concept of a continuous sea level, misunderstanding the work of mathematicians like Archimedes. Ultimately, Eratosthenes' reliance on questionable sources and his inconsistent reasoning weaken his credibility. His acceptance of unfounded tales and misunderstanding of scientific principles demonstrate significant flaws in his geographical methodology. |

|

| 4. In his Second Book, Eratosthenes revises geographical principles, introducing mathematics and physics, and asserting the earth's spherical shape. While some assumptions are commendable, his earth measurement is disputed by later scholars. Hipparchus, although critical, uses Eratosthenes’ meridian measurements. Eratosthenes measures the inhabited world's breadth from Meroë to Thule, totaling 38,000 stadia. However, the distance from Borysthenes to Thule is questionable. Pytheas, who claims Thule is north of Britain, is considered unreliable. The true length of Britain contradicts Pytheas' exaggerated figures. Hipparchus notes that the parallel through Britain and Byzantium align, but Eratosthenes' distance estimation from Thule lacks basis. Eratosthenes' errors extend to the world's length. He asserts that the inhabited world's length from India to Iberia is more than double its breadth, but his calculations are flawed. He incorrectly estimates various distances, including from India to the Pillars of Heracles, adding unnecessary stadia. He also claims the inhabited world extends east to west along a parallel, dismissing the potential for multiple inhabited zones within the temperate region. His adherence to the earth's spheroidal shape leads to unnecessary disputes with Homer. Eratosthenes discusses continents' boundaries, criticizing the division by rivers and isthmuses as impractical. He argues that practical boundary separation, like that of districts, is necessary but underestimates its importance in larger geopolitical contexts. His closing remarks propose evaluating people based on qualities rather than Greek and Barbarian distinctions, praising Alexander's inclusive approach. However, he overlooks that such distinctions reflect societal traits, not individual merits, aligning with Alexander's strategic inclusiveness. |

|

|

|

2 Eratosthenes wrong, Hipparchus' worse 5 143 2 Hrs.

|

| 2. In his treatise on Oceanus, Poseidonius addresses geography from both geographical and mathematical perspectives. He starts with the hypothesis that the earth is sphere-shaped, a view aligned with understanding the universe. This leads to the conclusion that the earth has five zones. Poseidonius credits Parmenides with the division into five zones but criticizes his description of the torrid zone. Parmenides overstates its breadth, extending it beyond the tropics into the temperate zones. Aristotle's division is also flawed, according to Poseidonius, because the "torrid" should only refer to the uninhabitable regions due to heat. He argues that more than half of the zone between the tropics is uninhabitable, as evidenced by the Ethiopians south of Egypt. Poseidonius' calculations refine these boundaries. From Syene to Meroë is 5,000 stadia, and from Meroë to the Cinnamon-producing Country is 3,000 stadia, totaling 8,000 stadia. Adding Eratosthenes' calculation of 8,800 stadia to the equator, Poseidonius finds that the torrid zone's breadth is about half the distance between the tropics. His measurements, which estimate the earth's circumference at 180,000 stadia, further support this. Poseidonius also criticizes using the "arctic circles" to define temperate zones, as they vary in visibility and aren't consistent everywhere. He proposes five zones based on celestial phenomena: two periscian (beneath the poles), two heteroscian (next to the tropics), and one amphiscian (between the tropics). For human purposes, he adds two narrow zones beneath the tropics, characterized by extreme heat and sparse vegetation, producing unique human and animal adaptations. Overall, Poseidonius' work emphasizes the need for accurate geographical and mathematical measurements in understanding the earth's zones. |

|

| 3. Polybius divides the Earth into six zones: two beneath the arctic circles, two between the arctic circles and the tropics, and two between the tropics and the equator. However, a five-zone division aligns better with physics and geography. This division accounts for celestial phenomena and atmospheric temperature, which are crucial for understanding the organization of plants, animals, and semi-organic matter. The five zones consist of two frigid zones (lacking heat), two temperate zones (moderate heat), and one torrid zone (excess heat). This division is harmonious with geography as it defines the habitable earth by the temperate zone. Boundaries on the west and east are set by the sea, while the south and north are defined by the nature of the air, making the central area well-suited for life due to moderate temperatures. Poseidonius criticizes the division into five zones, proposing seven, adding two narrow zones beneath the tropics that experience extreme heat, making them arid and barren, with unique fauna adapted to harsh conditions. He asserts that these areas differ significantly from regions further south, which are more temperate and fertile. Polybius's method of defining zones using the arctic circles is flawed because non-variable points should not be defined by variable points. Despite this, dividing the torrid zone into two parts is practical, as it aligns with the division of the earth into northern and southern hemispheres, each comprising three zones. Poseidonius also challenges Polybius's claim that the region under the equator is the highest point on Earth. He argues that a spherical surface cannot have a high point and that the equatorial region is not mountainous but rather level with the sea. Despite inconsistencies, Poseidonius suspects mountains beneath the equator influence rainfall patterns. Finally, Poseidonius dismisses the idea of a continuous ocean around the Earth, and critiques various claims of circumnavigation of Libya, deeming them unsupported by evidence. His skepticism extends to the credibility of explorers’ accounts, favoring empirical verification over anecdotal stories. |

|

| 4. Polybius critiques ancient geographers, particularly Dicaearchus, Eratosthenes, and Pytheas. Pytheas claimed to have explored Britain and the mysterious Thule, describing bizarre phenomena. Polybius doubts a poor man's ability to travel extensively, criticizing Eratosthenes for partially believing Pytheas, and suggesting Euhemerus, who only claimed one journey, is more credible. Poseidonius questions the reliability of Eratosthenes and Dicaearchus. He highlights errors in their distance measurements, particularly from the Peloponnesus to the Pillars and the Adriatic. Polybius corrects some errors but makes others, such as exaggerating distances in Iberia. He questions Polybius's method of comparing the lengths of continents by segments of the northern semicircle and insists on using fixed measures parallel to the equator. Polybius's division of Europe into promontories is seen as inadequate. He acknowledges Europe extends into several promontories but disputes Polybius's subdivisions. Polybius identifies three primary promontories but proposes five: Iberia, Italy, Greece, Thrace, and the region of the Cimmerian Bosporus. Poseidonius finds this division problematic due to the complex nature of these regions and the need for further subdivisions. Finally, Poseidonius points out Polybius's errors regarding Europe and Libya, stressing the need for corrections and additions. This critique justifies Poseidonius's endeavor to treat these subjects, emphasizing the necessity for accurate geographical understanding and the correction of past mistakes. |

|

| 5. Polybius critiques ancient geographers Dicaearchus, Eratosthenes, and Pytheas. He challenges Pytheas' claims of exploring Britain and Thule, which featured strange phenomena. Polybius doubts a poor man's ability to travel extensively and criticizes Eratosthenes for believing Pytheas' accounts of Britain, Iberia, and Gades. Polybius prefers Euhemerus' single journey claim over Pytheas' extensive exploration assertion, which he finds unbelievable. Poseidonius further critiques Eratosthenes and Dicaearchus, highlighting their errors in distance measurements, especially between Peloponnesus and the Pillars. Polybius corrects some mistakes but makes others, exaggerating distances in Iberia. He questions Polybius' method of comparing continent lengths using segments of the northern semicircle, advocating fixed measures parallel to the equator instead. Polybius' division of Europe into promontories is deemed inadequate. While acknowledging Europe's several promontories, Poseidonius disputes Polybius' subdivisions. Polybius identifies three primary promontories but proposes five: Iberia, Italy, Greece, Thrace, and the Cimmerian Bosporus region. Poseidonius finds this division problematic due to the complex nature of these regions, necessitating further subdivisions. Poseidonius also points out Polybius' errors regarding Europe and Libya, stressing the need for corrections and additions. This critique justifies Poseidonius' efforts to address these subjects accurately, emphasizing the necessity for precise geographical understanding and rectifying past mistakes. |

|

|

3 Iberia 5 115 1:38

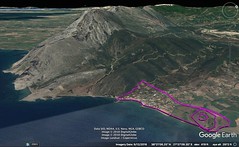

| 1. I have outlined geography generally, and now discuss parts of the inhabited world, starting with Europe and specifically Iberia. Iberia's larger part offers poor living conditions due to its mountainous and thinly-soiled regions, especially in the north, which is cold, rugged, and isolated by the ocean. Southern Iberia, particularly outside the Pillars, is fertile. Iberia resembles an ox-hide, stretching 6000 stadia in length from west to east and 5000 stadia in width from north to south. The Pyrenees form its eastern boundary, separating it from Celtica, which also varies in breadth. Iberia's most westerly point is the Sacred Cape, projecting 1500 stadia beyond Libya's headlands. Artemidorus likens the cape to a ship due to its shape and surrounding islands, but refutes Ephorus's claim of a temple of Heracles there, mentioning only stones turned by visitors. He also dismisses myths of the sun setting noisily and immediately bringing night in these regions. From the Sacred Cape, the western Iberian coast runs to the Tagus River's mouth, and the southern coast to the Anas River. Inland, the region houses Celtic peoples and some transplanted Lusitanians. The fertile Baetica region, named after the Baetis River, includes the ancient and wise Turdetanians, known for their historical records and alphabet. The Atlantic Ocean breaks in at the Pillars, forming a strait linking the interior and exterior seas. Near the strait, Mount Calpe rises steeply, resembling an island. Cities like Calpe, Menlaria, and Belon dot the coast, with Gades, renowned for its prosperity, located offshore. Iberia's coast also features the Port of Menestheus, estuaries, and the Baetis and Anas Rivers, leading to the Sacred Cape. |

|

| 2. Turdetania lies above the coast near the Anas River, through which the Baetis River flows. It is bounded by the Anas River to the west and north, Carpetania and Oretania to the east, and the Bastetanians to the south. The region includes over two hundred cities, with Corduba and Gades being the most prominent. Corduba, founded by Marcellus, is noted for its fertile soil and extensive territory, while Gades is famous for maritime commerce and its alliance with Rome. Other notable cities include Hispalis, Italica, and Ilipa, all situated along the Baetis River, which is navigable up to Corduba. Turdetania's rich soil and access to rivers facilitate extensive agricultural production and trade. The Baetis and Anas Rivers, along with numerous estuaries, support navigation and commerce. Turdetania is renowned for its exports, including grain, wine, olive oil, wax, honey, pitch, and wool. The region also boasts a significant fish-salting industry and abundant natural resources, including timber and salt quarries. The land is rich in metals, particularly silver, copper, and gold, with numerous mines scattered throughout. Turdetania's mineral wealth is so vast that it has been described as an "everlasting storehouse of nature." Mining techniques include washing gold-bearing sands and refining ores. Turdetania’s mines produce high-quality metals, and the region’s wealth has been known since ancient times, with historical references to its opulence. The Turdetanians have largely adopted Roman customs, with many cities now Latinized and integrated into Roman society. The Celtiberians, once considered brutish, have also embraced Roman culture, becoming part of the civilized world. |

|

| 3. Polybius defines six zones: two beneath the arctic circles, two between the arctic circles and the tropics, and two between the tropics and geography. This division relates to celestial phenomena and atmospheric temperature. The periscian, heteroscian, and amphiscian regions help determine constellations' appearances, while atmospheric temperature variations—excess heat, lack of heat, and moderate heat—affect plants and animals. The earth's division into five zones accounts for these temperature differences: two frigid zones with no heat, two temperate zones with moderate heat, and one torrid zone with excess heat. Polybius's use of the arctic circles to define zones is criticized for using variable points. He divides the torrid zone into two parts, aligning with the division of the earth into northern and southern hemispheres. This approach results in six zones, unlike other methods, which yield five. Eratosthenes suggested a third temperate zone at the equator due to its temperate climate, but Poseidonius criticized Polybius’s idea of the inhabited region under the equator being the highest, arguing that a spherical surface has no high point. Poseidonius recounts Eudoxus of Cyzicus’s voyage, claiming he found proof of circumnavigation around Libya. Eudoxus's journey included finding a ship’s prow from Gades, leading him to believe in the possibility of circumnavigation. Poseidonius supports the idea of a circumnavigable ocean, but his acceptance of Eudoxus's story is questionable. Poseidonius also discusses earth's changes due to natural phenomena and suggests that the Atlantis story might be based on fact. He speculates on migration due to sudden sea inundations and criticizes the traditional division of the world into continents, proposing a division based on zones and climates instead. However, he eventually agrees with the prevailing continental division. |

|

| 4. Polybius, in discussing Europe's geography, critiques previous geographers like Dicaearchus, Eratosthenes, and Pytheas. Pytheas claimed extensive travels in Britain and beyond, describing fantastical regions and coastlines. Polybius doubts the credibility of such claims, questioning how a private, impoverished individual could travel so extensively. He criticizes Eratosthenes for accepting Pytheas' accounts of Britain and Iberia but not those of Euhemerus, who only claimed to visit Panchaea. Polybius also disagrees with Eratosthenes' estimates of distances, particularly the 7,000 stadia from the Strait of Sicily to the Pillars of Hercules. Instead, he suggests it is much greater. Polybius believes errors exist in distance estimates, such as from Ithaca to Corcyra and from Epidamnus to Thessalonica, arguing they are longer than Eratosthenes claims. However, when estimating distances from Massilia to the Pillars and from the Pyrenees, he overestimates compared to Eratosthenes. He also finds fault with Eratosthenes' lack of knowledge about Iberia, noting inconsistencies in his descriptions of the Gauls and Iberians. Additionally, Polybius challenges the conventional understanding of Europe's length relative to Libya and Asia, arguing against the use of celestial positions for measurement. He critiques those who suggest the Tanaïs (Don) River flows from the summer sunrise or through the Caucasus. Polybius concludes that the geographical errors and misconceptions necessitate significant corrections and additions to the existing knowledge, underscoring the need for a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of the world's geography. |

|

| 5. Polybius critiques the geography of Europe by evaluating ancient geographers like Dicaearchus, Eratosthenes, and Pytheas. Pytheas claimed extensive travels and described fantastical regions and coastlines, which Polybius doubted. He questioned the credibility of such claims, considering Pytheas a poor individual, making such extensive travels improbable. Polybius also criticized Eratosthenes for accepting Pytheas' accounts of Britain and Iberia but rejecting Euhemerus' account of Panchaea. Polybius found errors in Eratosthenes' distance estimates, such as the 7,000 stadia from the Strait of Sicily to the Pillars of Hercules, suggesting it is much greater. He also pointed out inconsistencies in Eratosthenes' descriptions of the Gauls and Iberians, doubting his knowledge of Iberia. Additionally, Polybius challenged the understanding of Europe’s length relative to Libya and Asia, arguing against using celestial positions for measurements. He critiqued the suggestions that the Tanaïs (Don) River flows from the summer sunrise or through the Caucasus. In summary, Polybius emphasized the need for a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of the world’s geography, highlighting the significant errors and misconceptions in previous accounts and the importance of correct geographical measurements and descriptions. |

|

|

4 Transalpine Gaul 6 71 1 Hr

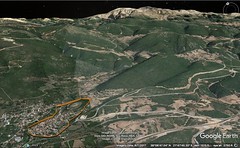

| 1. Transalpine Celtica is divided into three parts: Aquitani, Belgae, and Celtae. The Aquitani, distinct in language and physique, resemble the Iberians more than the Galatae. The Celtae and Belgae vary slightly in language and government. The region is bordered by the Pyrenees, the River Rhenus, the Alps, and the sea near Massilia and Narbo. Augustus Caesar divided Transalpine Celtica into four parts: the province of Narbonitis, Aquitani, and two parts under the boundaries of Lugdunum and Belgae. The country is watered by rivers flowing from the Alps, Cemmenus, and Pyrenees, supporting agriculture and transport. The Rhodanus River, with its many tributaries, is significant for navigation and connects with the Mediterranean Sea. Narbonitis resembles a parallelogram, bordered by the Pyrenees, Cemmenus, Alps, and the sea. Massilia, a Phocaean-founded city, lies on a rocky promontory with a well-fortified harbor. The city's government is aristocratic, with an Assembly of six hundred men. The region's economy is based on seafaring and trade, supplemented by agriculture in surrounding plains. Narbonitis' seaboard is notable for its natural features, such as the "Stony Plain" and the unique "dug mullets" found in its marshes. The region's rivers facilitate trade and transport, linking the interior to both the Mediterranean and the Atlantic. The country is fertile, producing various crops and livestock. The inhabitants, known for their fighting spirit, have adapted to farming under Roman rule. Narbonitis, rich in history and culture, continues to thrive with its strategic location and natural resources. |

|

| 2. The Aquitani, distinct from the Galatic tribes in physique and language, resemble the Iberians. Their territory spans from the Garumna River to the Pyrenees and includes fourteen Galatic tribes between the Garumna and Liger Rivers. These rivers are parallel to the Pyrenees, forming parallelograms bounded by the ocean and the Cemmenus Mountains. The Aquitani live mostly along the ocean, with some tribes reaching the Cemmenus Mountains. The Garumna discharges between the Bituriges Vivisci and the Santoni, while the Liger flows between the Pictones and the Namnitae. The Aquitani's ocean-coast is sandy, growing millet but few other crops. The Tarbelli in the region hold significant gold mines, with gold found in large slabs and nuggets. The interior regions, like those of the Convenae and Auscii, have better soil and notable features such as hot springs and good agricultural land. Tribes between the Garumna and Liger include the Elui, Vellavii, Arverni, Lemovices, Petrocorii, Nitiobriges, Cadurci, Bituriges Cubi, Santoni, Pictones, Ruteni, and Gabales. These regions have iron works, linen factories, and silver mines. The Romans have granted "Latin right" to some Aquitani tribes, enhancing their status. The Arverni, situated on the Liger, have a history of resisting Roman conquest with large armies, including notable battles against Caesar, Maximus Aemilianus, and Dometius Ahenobarbus. They once controlled extensive territories from Narbo to the Pyrenees, the ocean, and the Rhenus. Their wealth and power are exemplified by the extravagance of their leaders, such as Luerius. |

|

| 3. The Aquitanian division and Narbonitis extend to the Rhenus, starting from the Liger and the Rhodanus near Lugdunum. This region is divided: the upper parts near the river sources belong to Lugdunum, while the rest, including coastal areas, are under the Belgae. Lugdunum, a city at the confluence of the Arar and the Rhodanus, is a Roman stronghold and a populous emporium where Roman governors mint coins. A temple dedicated to Caesar Augustus by all the Galatae is nearby, featuring an altar with inscriptions of sixty tribes and their images. The Segusiavi tribe lives between the Rhodanus and the Dubis. Other tribes stretch towards the Rhenus, bounded by the Dubis and Arar rivers. The Sequana River, also originating in the Alps, flows to the ocean and is known for its fine salted hog-meat. The Aedui tribe, with their city Cabyllinum on the Arar, were the first to ally with the Romans. The Sequani, often in conflict with the Aedui and Romans, demonstrated significant power by aligning with the Germans. The Elvetii, near the Rhenus's sources on Mount Adula, have been reduced in number but were once powerful. The Rhenus flows through marshes and a large lake, contrary to claims of its exaggerated length. Beyond the Elvetii and Sequani, the Aedui, Lingones, Mediomatrici, and Tribocchi tribes dwell. The Treveri, who constructed a bridge for the Germanic war, live along the Rhenus. The Nervii, Menapii, and other tribes extend to the river's mouth, living in forests like Arduenna, which served as defensive refuges. All these tribes are now at peace and under Roman control. |

|

| 4. After the aforementioned tribes, the remaining Belgae tribes live on the ocean coast. The Veneti, who fought a naval battle against Caesar, were prepared to hinder his voyage to Britain, using their emporium there. Caesar defeated them by hauling down their sails with pole-hooks. The Veneti built their ships with broad bottoms, high sterns, and high prows using oak and seaweed to prevent drying. The Osismii, who live on a promontory projecting into the ocean, are also notable among the Belgae. The whole Gallic race is warlike, high-spirited, and quick to battle, though otherwise simple and not ill-mannered. They gather quickly for battle, making them easy to defeat with stratagems. They are physically large and numerous, easily provoked to defend their neighbors. Currently, they live in peace under Roman command, but historically they were more autonomous. The Belgae, divided into fifteen tribes, are the bravest, particularly the Bellovaci and the Suessiones. The Belgae could resist the Germanic Cimbri and Teutones. Their population was large, with about 300,000 able to bear arms. They wore the "sagus," had long hair, and wore tight breeches. Their armor included long sabres and oblong shields. They had large flocks and herds, supplying Rome with "sagi" and salted meat. Their governments were mostly aristocratic, with one leader annually chosen for war. Three classes of men held in high honor among the Gauls: the Bards (singers and poets), the Vates (diviners and natural philosophers), and the Druids (moral philosophers). The Druids were trusted to decide private and public disputes and believed men's souls and the universe were indestructible. The Gallic people are also known for their witlessness, boastfulness, and fondness for ornaments. They wore golden chains and bracelets, and their dignitaries wore garments sprinkled with gold. Their customs included hanging enemy heads from their horses and homes. The Romans stopped such customs and human sacrifices. |

|

| 5. Britain is triangular, with its longest side parallel to Celtica, both about 4,300 stadia long. The Celtic length extends from the Rhenus to the northern Pyrenees, while Britain's extends from Cantium to the western end opposite the Aquitanian Pyrenees. The shortest distance between the Pyrenees and Rhenus is around 5,000 stadia. There are four main passages from the mainland to the island, starting from the rivers Rhenus, Sequana, Liger, and Garumna. Voyages from near the Rhenus often start from the Morini coast. Caesar used Itium as a naval station for his voyage to Britain. Most of Britain is flat and forested, with some hilly regions. It produces grain, cattle, gold, silver, and iron, along with hides, slaves, and hunting dogs. The Britons are taller than the Celti but less muscular. They are somewhat primitive in agricultural practices and use chariots in war, similar to some Celti. Their cities are forest enclosures for temporary habitation. The climate is rainy, with frequent fogs. Caesar crossed to Britain twice but did not venture far due to local conflicts and ship losses. He won victories and returned with hostages, slaves, and booty. Some British chieftains sought Augustus's friendship, dedicating offerings in the Capitol and making the island virtually Roman property. They easily submit to duties on imports and exports, making garrisoning unnecessary. Besides smaller islands, there is a large island, Ierne, north of Britain, with more savage inhabitants who are rumored to practice cannibalism and incest. Information about Thule is uncertain, with much of Pytheas's accounts considered fabricated. However, some details align with what might be expected near the frozen zone, like scarce animal life and reliance on

herbs, roots, and stored grain. |

|

|

5 North Italy 4 89 1:15

| 1. After the foothills of the Alps comes the beginning of what is now Italy. Initially, only Oenotria was called Italy, extending from the Strait of Sicily to the Gulfs of Tarentum and Poseidonia. The name Italy later expanded to include areas up to the Alps and parts of Ligustica and Istria. The name spread due to the prosperity of the original Italians, who extended it to neighboring peoples until the Roman conquest. The Romans later included the Cisalpine Galatae and the Heneti, calling all Italiotes and Romans, and established many colonies. Italy is roughly triangular, with its vertex at the Strait of Sicily and its base at the Alps. The Alps form a curved base, with a central gulf near the Salassi and extending to the Adriatic and Ligurian seaboards. A large plain lies at the base of the Alps, divided by the Padus River into Cispadana and Transpadana. Cispadana lies next to the Apennine Mountains and Liguria, while Transpadana is inhabited by Ligurian and Celtic tribes. The Celts are related to the Transalpine Celts, while the Heneti are believed to be descendants of the Paphlagonian Heneti. The country is rich in rivers and marshes, particularly the Heneti's part, which experiences ocean-like tides. This area, intersected by channels and dikes, has cities surrounded by water and fertile plains drained for agriculture. Notable cities include Patavium, Ravenna, and Altinum, which are connected by inland waterways. Patavium is particularly prosperous, known for its manufacturing and large army. Ravenna is built on wood and surrounded by rivers, making it healthful despite being in a marsh. |

|

| 2. Liguria and Tyrrhenia: The Second Portion is Liguria, in the Apennines, between Celtica and Tyrrhenia. Its inhabitants live in villages, quarrying stones and farming rough land. The Third Portion is Tyrrhenia, extending to the River Tiber and bounded by the Tyrrhenian and Sardinian Seas. The Tiber flows from the Apennines, traversing Tyrrhenia and separating it from Ombrica, the Sabini, and part of Latium, which stretches to the coastline near Rome. The Latini's country extends from Ostia to Sinuessa, reaching Campania and the Samnite mountains. The Sabini lie between the Latini and Ombrici, extending to the Samnite mountains and Apennines. The Ombrici extend over the mountains to Ariminum and Ravenna. Tyrrheni: The Tyrrheni, called "Etrusci" and "Tusci" by Romans, were named after Tyrrhenus, who led Lydian colonists. Initially united and powerful, they later fragmented into separate cities due to neighboring pressures. Post-Rome's founding, Demaratus brought Corinthians to Tarquinii, influencing Rome’s early culture. The Tyrrheni thrived and were known for their contributions to Roman customs, such as the fasces and sacrificial rites. Notable achievements include the Caeretani defeating the Galatae and saving Rome's sacred fire and Vestal priestesses during a Gallic invasion. Geography and Cities: Tyrrhenia's coast from Luna to Ostia is about 2,500 stadia long. Key cities include Luna, with its significant harbor and marble quarries, and Pisa, founded by Greek settlers from the Peloponnesus. Volaterrae is situated in a ravine, known for its resistance against Sulla’s forces. Poplonium, located on a promontory, has an ancient harbor and historical mines. Ravenna, built on wood and surrounded by rivers, was a healthful city used for training gladiators. The Tyrrheni also inhabited areas rich in lakes, hot springs, and agricultural lands. |

|

| 3. The Sabini live in a narrow region stretching about a thousand stadia from the Tiber and Nomentum to the Vestini. Their few cities include Amiternum, Reate (near the cold springs of Cotiliae), and Foruli, a rocky elevation more suited for revolt than habitation. Cures, once significant, is now a small village but notable as the home of two Roman kings, Tatius and Numa Pompilius. The Sabini region is fertile, producing olives, vines, acorns, and renowned for Reate-breed mules. The Sabini are ancient, indigenous people, with the Picentini, Samnitae, Leucani, and Brettii as their descendants. They were known for their bravery and have endured through time. The Latin region, including Rome, originally comprised several tribes like the Aeci, Volsci, Hernici, Rutuli, and aborigines. Aeneas, after landing at Laurentum, allied with Latinus against the Rutuli of Ardea, leading to the founding of Lavinium and Alba. The Romans, Latini, and Albani jointly offered sacrifices to Zeus on Mount Albanus. The region expanded under Roman rule, eventually including Campania, the Samnitae, and the Peligni. Latium is fertile but some coastal and marshy areas are less so. Cities like Ostia, Antium, and Circaeum were important, with Ostia founded by Ancus Marcius and Antium being a resort for Roman rulers. Inland, Rome, founded out of necessity rather than choice, expanded through fortifications by successive rulers. Augustus improved city safety, reduced building heights, and organized fire protection. Rome's natural blessings include abundant materials, and the foresight in constructing roads, aqueducts, and sewers has added to its prosperity. Notable infrastructure improvements and public works were carried out by Agrippa, Caesar, and other leaders, making Rome a city of remarkable structures and resources. |

|

| 4. The country of the Sabini extends lengthwise up to a thousand stadia from the Tiber and Nomentum to the Vestini. Their few cities, including Amiternum and Reate, have suffered due to constant wars. Notably, Cures, once significant, is now a small village. The Sabini region is fertile, producing olives, vines, and renowned Reate-breed mules. The Sabini are an ancient, indigenous people, with the Picentini, Samnitae, Leucani, and Brettii as their descendants. They are known for their bravery and have endured through time. The Latin region, including Rome, initially comprised several tribes such as the Aeci, Volsci, Hernici, and Rutuli. Aeneas, after landing at Laurentum, allied with Latinus against the Rutuli of Ardea, leading to the founding of Lavinium and Alba. The Romans, Latini, and Albani jointly offered sacrifices to Zeus on Mount Albanus. Under Roman rule, the region expanded to include Campania, the Samnitae, and the Peligni. Latium is fertile, but some coastal and marshy areas are less so. Cities like Ostia, Antium, and Circaeum were important, with Ostia founded by Ancus Marcius and Antium becoming a resort for Roman rulers. Rome, founded out of necessity, expanded through fortifications by successive rulers. Augustus improved city safety, reduced building heights, and organized fire protection. Rome's natural blessings include abundant materials, and foresight in constructing roads, aqueducts, and sewers has added to its prosperity. Notable infrastructure improvements and public works were carried out by Agrippa, Caesar, and other leaders, making Rome a city of remarkable structures and resources. |

|

| 5. After the Sabini, the Latini, including Rome, extended their power over surrounding tribes. The Latini originally comprised several tribes such as the Aeci, Volsci, Hernici, and Rutuli. Aeneas, after landing at Laurentum, allied with Latinus against the Rutuli of Ardea, leading to the founding of Lavinium and Alba. The Romans, Latini, and Albani jointly offered sacrifices to Zeus on Mount Albanus. Under Roman rule, the region expanded to include Campania, the Samnitae, and the Peligni. Latium is fertile but some coastal and marshy areas are less so. Cities like Ostia, Antium, and Circaeum were important, with Ostia founded by Ancus Marcius and Antium becoming a resort for Roman rulers. Inland, Rome, founded out of necessity rather than choice, expanded through fortifications by successive rulers. Augustus improved city safety, reduced building heights, and organized fire protection. Rome's natural blessings include abundant materials, and foresight in constructing roads, aqueducts, and sewers has added to its prosperity. Notable infrastructure improvements and public works were carried out by Agrippa, Caesar, and other leaders, making Rome a city of remarkable structures and resources. |

|

|

6 South Italy. 4 74 1:02

| 1. After the mouth of the Silaris River lies Leucania, featuring the temple of the Argoan Hera, built by Jason. Close by is Poseidonia. Sailing past the gulf, one reaches Leucosia, an island named after a Siren from myth. Near this island is a promontory forming the Poseidonian Gulf. Beyond this is the city of Elea, founded by Phocaeans and home to philosophers Parmenides and Zeno. Despite its poor soil, Elea thrived due to its governance and salt fish industry.

Next comes the promontory of Palinurus, followed by Pyxus, and then Laüs, a city founded by Sybaritae. The entire Leucanian coast stretches 650 stadia. The Leucani occupied these lands after displacing the Chones and Oenotri, but were later overshadowed by Greek colonies and the Carthaginians. As a result, much of Magna Graecia, once dominated by Greeks, fell into barbarism, with regions now controlled by Romans, Leucani, Brettii, and Campani.

The interior settlements, like Petelia founded by Philoctetes, remain significant. The Leucani, originally Samnite, governed democratically except during wars. The Brettii, revolting from the Leucani, established themselves during Dio's expedition. Temesa, initially an Ausonian settlement, and other cities like Terina and Consentia, faced Hannibal’s destruction or Roman conquest. Near Consentia is Pandosia, where Alexander the Molossian met his end, deceived by an oracle. Hipponium, renamed Vibo Valentia by the Romans, and other cities like Medma and Metaurus hold historical significance, showcasing the region’s rich yet turbulent history. |

|

| 2. Sicily, triangular in shape, was once called "Trinacria" and later "Thrinacis." Its three capes are Pelorias, Pachynus, and Lilybaeum, facing different directions: Pelorias towards the strait, Pachynus towards the east, and Lilybaeum towards Libya. The longest side, from Lilybaeum to Pelorias, is about 1,720 stadia. The entire coastline, as Poseidonius states, is about 4,000 stadia.

The main cities along the strait side are Messene, Tauromenium, Catana, and Syracuse. Ancient cities like Naxus and Megara have disappeared. Messene, founded by Peloponnesian Messenians, is now predominantly known for its wine, which rivals Italy's best. Catana, more populous, was originally founded by Naxians. Hiero, tyrant of Syracuse, once repopulated it, calling it Aetna. The city of Aetna, situated near the mountain, often suffers from volcanic activities.

Syracuse, founded by Archias from Corinth, became immensely wealthy. The city, originally sprawling over five towns, was partly restored by Augustus Caesar. Ortygia, connected to the mainland, hosts the famous fountain of Arethusa.

Sicily's interior features Enna, known for its temple of Demeter, and the lofty Eryx, home to a revered temple of Aphrodite. Many ancient cities, like Himera, Gela, and Selinus, have been deserted and turned into pastures. The region's fertility, particularly in grain, honey, and saffron, makes it a vital supplier to Rome.

Near Centoripa, the town of Aetna serves as a base for ascents up Mount Etna. The mountain's summit features shifting volcanic activity, including ash eruptions and lava flows. The Nebrodes Mountains, lower yet broader, rise opposite Etna. The entire island is rich with hot springs and underground rivers, showcasing its volcanic nature. |

|

| 3. Now that I have traversed the regions of Old Italy as far as Metapontium, I must speak of those that border on them. Iapygia, also called Messapia by the Greeks, borders them. The natives call one part (near the Iapygian Cape) Salentini, and the other Calabri. North of these are the Peucetii and Daunii. The whole country after Calabri is called Apulia. Messapia forms a peninsula enclosed by the isthmus from Brentesium to Taras, three hundred and ten stadia. The distance from Metapontium to Taras is about two hundred and twenty stadia.

Taras has a large, beautiful harbor, enclosed by a bridge and one hundred stadia in circumference. The city, partly forsaken, still has a noteworthy part near the acropolis, featuring a gymnasium and a large marketplace with a bronze colossus of Zeus. The acropolis, though looted by Carthaginians and Romans, still holds significant remnants.

Antiochus recounts Taras' founding: During the Messenian war, Spartans who did not participate were enslaved and their children, born during the expedition, called Partheniae, deprived of citizenship. They plotted against the free citizens, but their plot was discovered. The Partheniae, under Phalanthus, were sent to found a colony. They settled in Taras, welcomed by the natives and some Cretans. The city was named after a hero.

At one time, Taras was powerful, with a strong democratic government, a large fleet, and significant military force. However, luxury led to poor governance. They hired foreign generals, including Alexander the Molossian, Archidamus, Cleonymus, Agathocles, and Pyrrhus, but could not maintain stability. Eventually, they were deprived of their freedom during the wars with Hannibal, received a Roman colony, and now live more peacefully. |

|

| 4. Italy, resembling an island, is securely guarded by seas and mountains, making it well-protected. Most of its coast is harbourless, aiding in defense, while its few harbors are excellent for trade and counter-attacks. Its diverse climates support a variety of life, contributing to its strength. The Apennine Mountains run its length, providing both fertile plains and hills. Italy's many rivers, lakes, and springs, along with abundant resources, enhance its livability. Centrally located between major regions, it is well-suited for leadership and can easily interact with surrounding areas.

The Romans, after founding Rome, wisely continued under kings until ejecting the last Tarquin and establishing a government mixing monarchy and aristocracy. They expanded by dealing with neighboring peoples, eventually making all of Latium their subjects and stopping the Tyrrheni and Celts. They subdued the Samnites, Tarentines, Pyrrhus, and others in Italy before moving on to Sicily and Carthage. They fought three wars against Carthage, ultimately destroying it and expanding into Libya and Iberia. Conquests extended to Greece, Macedonia, and Asia, subduing kings like Antiochus, Philip, and Perseus. They also subdued Illyrians, Thracians, Iberians, and Celts, with significant campaigns led by Julius Caesar and Augustus.

Augustus Caesar brought peace and prosperity, continued by his successor Tiberius and his sons Germanicus and Drusus. Under their rule, Italy thrived, despite internal factions, due to their effective governance. |

|

|

|

7 Central Europe. 8 114 1:35

| 1. Italy is uniquely positioned and well-guarded by seas and mountains, making it nearly impenetrable. It has a mix of climates, fostering a variety of life, and boasts numerous rivers, lakes, and mineral springs. Italy's geography, extending north to south, includes the Apennine Mountains, which offer both fertile plains and hill regions. Its natural resources, including mines and fertile lands, contribute to its abundance. Centrally located between major regions, it benefits from its proximity to both large races and Greece, facilitating hegemony.

After Rome's founding, the Romans wisely maintained a monarchy, later shifting to a mixed government after expelling the last Tarquin king. They expanded their territory by incorporating neighboring regions, defeating the Latins, Tyrrhenians, Celts, Samnites, and others. They moved beyond Italy, conquering Sicily and fighting Carthage in three wars, ultimately destroying it and expanding into Libya and Iberia. Their conquests included Greece, Macedonia, and parts of Asia, defeating notable kings like Antiochus, Philip, and Perseus.

The Romans continued expanding into Illyria, Thrace, Iberia, and Celtica, with significant campaigns led by Julius Caesar and Augustus. Augustus Caesar brought unprecedented peace and prosperity, which continued under his successor Tiberius and his sons, Germanicus and Drusus. Despite internal factions, their effective governance ensured the stability and success of the Roman Empire. |

|

| 2. The accounts of the Cimbri contain inaccuracies and improbabilities. It is unlikely that they became nomadic due to a great flood-tide, as they still occupy their original lands. They even sent a sacred kettle to Augustus, seeking friendship and amnesty for past offenses. The notion that they left their homes because of natural, daily occurring tides is absurd. Assertions of a catastrophic flood are fabrications; ocean tides are regular and periodic. The idea that the Cimbri fought the tides or that Celts trained to face tidal destruction is also unfounded. Regular tidal patterns would have made such misunderstandings improbable.

Poseidonius criticizes these tales, suggesting the Cimbri were a piratical people who ventured as far as Lake Maeotis and that the "Cimmerian" Bosporus was named after them, equating "Cimmerii" with "Cimbri." He notes that the Cimbri, repulsed by the Boii in the Hercynian Forest, moved to the Ister, encountering various Galatae tribes. They allied with the Helvetii, whose wealth prompted them to join the Cimbri. All these groups were eventually subdued by the Romans.

The Cimbri had a custom involving their priestesses, who, clad in white with bronze girdles, performed ritual sacrifices of prisoners. These priestesses would prophesy from the blood and entrails of the victims, and during battles, they would create unearthly noises by beating on hide-covered wagons.

The Germans, extending from the Rhenus to the Albis, include the Sugambri and Cimbri, but the regions beyond the Albis remain largely unknown to the Romans. The extent and nature of the lands beyond Germany and their inhabitants are still a mystery. |

|

| 3. The Cimbri, a Germanic tribe, are often misunderstood in historical accounts. Contrary to some stories, they did not become nomadic due to flood-tides; they still inhabit their ancestral lands. They even sought friendship with Augustus, sending him a sacred kettle. The idea that they fled due to natural tidal patterns is absurd, given the regularity of such tides. Poseidonius, a historian, criticizes these tales and suggests the Cimbri were a piratical people who traveled far, even to Lake Maeotis. He theorizes that the "Cimmerian" Bosporus was named after the Cimbri, known as "Cimmerii" by the Greeks. The Cimbri, after being repulsed by the Boii in the Hercynian Forest, moved towards the Ister and allied with the Helvetii. Both were eventually subdued by the Romans.

The Cimbri had unique customs, involving priestesses who performed sacrificial rituals. These priestesses, dressed in white with bronze girdles, would prophesy from the blood and entrails of prisoners. The Germans, extending from the Rhenus to the Albis, include tribes like the Sugambri and the Cimbri. However, regions beyond the Albis remain largely unknown to the Romans.

The Getae, another significant group, lived on both sides of the Ister River and were sometimes considered Thracians. Poseidonius notes that some Mysians, known for their peaceful, religious life, abstained from eating living things and lived on honey, milk, and cheese. This peacefulness earned them the titles "god-fearing" and "capnobatae." The region also hosted various tribes, including the Bastarnians and Roxolani, who lived nomadic lifestyles.

Despite historical inaccuracies, it is clear that the Cimbri, Getae, and related tribes had complex societies with unique customs and interactions with neighboring cultures and the Romans. |

|

| 4. The isthmus separating Lake Sapra from the sea, forming the Tauric Chersonese, is forty stadia wide. Lake Sapra, part of Lake Maeotis, is very marshy, making it difficult to navigate with larger boats. The gulf contains islands, shoals, and reefs. Sailing out of the gulf, one encounters a small city and harbor belonging to the Chersonesites. Nearby is a cape housing the city of the Heracleotae, known as Chersonesus. This city features the temple of the Parthenos and three harbors. The Old Chersonesus, now in ruins, once served as a pirate haven. The harbor Symbolon Limen and Ctenus Limen form a narrow isthmus enclosing the Little Chersonesus.

This city became subject to Mithridates Eupator after being sacked by barbarians. Mithridates also established control over the Bosporus region. The city of the Chersonesites remains under the control of the Bosporus rulers. The coast from Symbolon Limen to Theodosia, about a thousand stadia, is rugged and stormy, with a promontory called Criumetopon opposite the Paphlagonian promontory Carambis, dividing the Euxine Pontus into two seas.

The city Theodosia, in a fertile plain, features a large harbor. The fertile region extends to Panticapaeum, the Bosporian metropolis. Panticapaeum, a Miletian colony, lies on a hill with a harbor and docks. It was ruled by the dynasty of Leuco, Satyrus, and Parisades until the last Parisades surrendered to Mithridates due to pressure from barbarians. The Bosporian kingdom has since been subject to the Romans, spanning both Europe and Asia.

The mouth of Lake Maeotis, the Cimmerian Bosporus, is about seventy stadia wide, with crossings from Panticapaeum to Phanagoria. The Tanaïs River, opposite the Bosporus, flows into the lake, forming part of the boundary between Asia and Europe. |

|

| 5. The remainder of Europe lies between the Ister and the encircling sea, starting at the recess of the Adriatic and extending to the Sacred Mouth of the Ister. This region includes Greece, Macedonian, and Epeirote tribes, extending to the Ister and seas on either side. To the north are parts between the Ister and the mountains, while to the south are Greece and adjoining barbarian lands. The Haemus Mountain, near the Pontus, is the largest and highest in this region, dividing Thrace. Polybius incorrectly claimed that both seas are visible from Haemus, as the distance to the Adriatic is too great.

The country also includes Illyrian, Paeonian, and Thracian mountains, which are parallel to the Ister. This division separates the northern parts from those towards Greece and barbarian lands extending to the mountains. The Illyrian regions connect with Italy, the Alps, and territories of the Germans, Dacians, and Getans. The Dacians devastated part of this country, subduing the Celtic tribes Boii and Taurisci. The Pannonii occupy the remaining land, reaching Segestica and the Ister, with territories extending further.

Segestica, a Pannonian city, lies at the confluence of navigable rivers and is a strategic base for wars against the Dacians. Rivers flow from Mount Ocra, carrying merchandise to Segestica from Italy. Pannonian tribes include the Breuci, Andizetii, Ditiones, Peirustae, Mazaei, and Daesitiatae, extending as far south as Dalmatia and Ardiaei land. The mountainous country stretching from the Adriatic recess to the Rhizonic Gulf and Ardiaei land is Illyrian, positioned between the sea and P

annonian tribes. |

|

| 6. The remaining part of Europe between the Ister and the mountains includes the Pontic seaboard from the Sacred Mouth of the Ister to the mouth at Byzantium. Starting at the Sacred Mouth of the Ister and keeping the coast on the right, one reaches Ister, a small town founded by the Milesians, after 500 stadia, then Tomis after 250 stadia, followed by Callatis, a colony of the Heracleotae, after 280 stadia, and Apollonia, a Milesian colony, after 1,300 stadia. Between Callatis and Apollonia are Bizone, Cruni, Odessus (a Milesian colony), and Naulochus (a small town of the Mesembriani).

The Haemus Mountain, reaching the sea near Mesembria (a Megarian colony), divides the coast. Apollonia is also home to Cape Tirizis, used as a treasury by Lysimachus. From Apollonia to the Cyaneae, the distance is about 1,500 stadia, passing Thynias, Anchiale, Phinopolis, and Andriaca. Salmydessus, a desert, stony beach, extends to the Cyaneae over 700 stadia. The Cyaneae are two islets near the mouth of the Pontus, separated by 20 stadia, and 20 stadia from the temples of Byzantines and Chalcedonians.

The narrowest part of the mouth of the Euxine is five stadia wide, leading to the Propontis. From this narrow point to the harbor "Under the Fig-tree" is 35 stadia, and five stadia further to the Horn of the Byzantines, a gulf resembling a stag's horn, extending 60 stadia. Pelamydes fish, hatched in Lake Maeotis, rush to these gulfs, where they are easily caught. This abundance benefits Byzantium, providing significant revenue, while Chalcedonians, on the opposite shore, miss out on this wealth. |

|

| 7. The remaining part of Europe between the Ister and the mountains includes the Pontic seaboard from the Sacred Mouth of the Ister to the mouth at Byzantium. Starting at the Sacred Mouth of the Ister and keeping the coast on the right, one reaches Ister, a small town founded by the Milesians, after 500 stadia, then Tomis after 250 stadia, followed by Callatis, a colony of the Heracleotae, after 280 stadia, and Apollonia, a Milesian colony, after 1,300 stadia. Between Callatis and Apollonia are Bizone, Cruni, Odessus (a Milesian colony), and Naulochus (a small town of the Mesembriani).

The Haemus Mountain, reaching the sea near Mesembria (a Megarian colony), divides the coast. Apollonia is also home to Cape Tirizis, used as a treasury by Lysimachus. From Apollonia to the Cyaneae, the distance is about 1,500 stadia, passing Thynias, Anchiale, Phinopolis, and Andriaca. Salmydessus, a desert, stony beach, extends to the Cyaneae over 700 stadia. The Cyaneae are two islets near the mouth of the Pontus, separated by 20 stadia, and 20 stadia from the temples of Byzantines and Chalcedonians.

The narrowest part of the mouth of the Euxine is five stadia wide, leading to the Propontis. From this narrow point to the harbor "Under the Fig-tree" is 35 stadia, and five stadia further to the Horn of the Byzantines, a gulf resembling a stag's horn, extending 60 stadia. Pelamydes fish, hatched in Lake Maeotis, rush to these gulfs, where they are easily caught. This abundance benefits Byzantium, providing significant revenue, while Chalcedonians, on the opposite shore, miss out on this wealth. |

|

| 8. In earlier times, an oracle existed near Scotussa, a city of Pelasgiotis in Thessaly, and was transferred to Epirus after a fire, following an oracle given by Apollo at Dodona. The oracle used symbols rather than words, similar to Zeus Ammon in Libya. Observations and prophecies were made from the flight of three pigeons. Among the Molossians and Thesprotians, old women were called "peliai" and old men "pelioi," suggesting the Peleiades were not birds but old women associated with the temple.

The sacred oak tree in Dodona was revered as the earliest plant and first to supply food. Doves, observed for augury, were also significant in the temple rituals. The term "tomouroi" likely evolved from "tomarouroi," indicating temple guardians. The oracle, initially under the Thesprotians, later came under the Molossians, and the interpreters of Zeus were called "tomouroi."

A proverbial phrase, "the copper vessel in Dodona," originated from a copper vessel and a copper scourge dedicated by the Corcyraeans. The scourge's bones struck the vessel continuously when swung by the wind, producing prolonged tones, leading to the term "the scourge of the Corcyraeans."

Paeonia lies east of these tribes and west of the Thracian mountains, north of Macedonia, and south of the Autariatae, Dardanii, and Ardiaei. It stretches as far as the Strymon River. The Haliacmon River flows into the Thermaean Gulf. Orestis is a large mountainous area extending to Mount Corax in Aetolia and Mount Parnassus, inhabited by various tribes, including the Orestae and Tymphaei. |

|

|

|

|

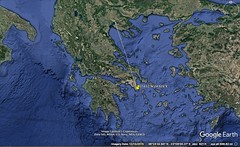

8 Peloponnesus. 8 112 1:35

| 1. I began my description of Europe with its western parts between the inner and outer sea, covering all the barbarian tribes up to the Tanaïs and part of Greece, including Macedonia. Now, I will describe the remainder of Greece. This topic was first treated by Homer and subsequently by others in treatises like "Harbours," "Coasting Voyages," and "General Descriptions of the Earth." Notable historians such as Ephorus and Polybius, as well as physicists and mathematicians like Poseidonius and Hipparchus, have also addressed it. Homer's work requires critical inquiry since it is poetic and reflects ancient times, not the present.

I will begin with the Greek peoples following the Epeirotes and Illyrians, covering the Acarnanians, Aetolians, and Ozolian Locrians, then the Phocians and Boeotians. Opposite these regions across the sea is the Peloponnesus, shaping and being shaped by the Corinthian Gulf. After Macedonia, I will cover Thessaly and the countries outside and inside the Isthmus.

Greece once had many tribes, corresponding to its four dialects: Ionic, Doric, Aeolic, and Attic. Over time, these dialects evolved due to geographic and social factors. The Ionians and Aeolians predominated in different regions, with Dorians later mixing with other tribes.

Ephorus begins his description with Acarnania, as it borders the Epeirotes. Using the sea as a guide, I will describe Greece starting from the Sicilian Sea, extending to the Corinthian Gulf and the Peloponnesus. Greece is divided into two main parts: inside and outside the Isthmus. The Peloponnesus, resembling an acropolis, is noted for its topography, power, and historical significance. This region features several significant peninsulas, starting with the Peloponnesus itself. The sequence of peninsulas provides a natural order for describing the geography of Greece, beginning with the smallest but most famous. |

|

| 2. The Peloponnesus resembles a plane tree leaf, with its length and breadth both about 1400 stadia. It spans from Chelonatas in the west, through Olympia and Megalopolis, to the Isthmus in the east. The width, from Maleae in the south through Arcadia to Aegium in the north, is similar. According to Polybius, the perimeter, without following the gulf sinuosities, is 4000 stadia; Artemidorus adds 400 more. Following the sinuosities, it's over 5600 stadia. The Isthmus, where ships are hauled from one sea to the other, is 40 stadia wide.

The western part is occupied by the Eleians and Messenians, washed by the Sicilian Sea. The Eleian country curves north to the Corinthian Gulf as far as Cape Araxus, facing Acarnania and its coastal islands—Zacynthos, Cephallenia, Ithaca, and the Echinades, including Dulichium. The Messenian country extends south to the Libyan Sea, near Taenarum. Next is Achaea, facing north along the Corinthian Gulf to Sicyonia, followed by Sicyon and Corinth, the latter extending to the Isthmus. Then come Laconia and Argolis, also reaching the Isthmus. The gulfs here are the Messenian, Laconian, Argolic, Hermionic, and Saronic. The first two are filled by the Libyan Sea, the others by the Cretan and Myrtoan Seas. The Saronic Gulf is also called "Strait" or "Sea." Arcadia, in the peninsula's interior, borders all these regions.

The Corinthian Gulf starts at the Evenus or Acheloüs River and Araxus, where the shores draw closer, meeting at Rhium and Antirrhium, separated by a five-stadia strait. Rhium, in Achaea, has a Poseidon temple. Antirrhium is on the Aetolia-Locris boundary. The shoreline widens again into the Crisaean Gulf, ending at Boeotia and Megaris. The Corinthian Gulf's perimeter from the Evenus to Araxus is 2230 stadia, or slightly more from the Acheloüs. The coast from the Acheloüs to the Evenus is Acarnanian, then Aetolian to Antirrhium, and Phocian, Boeotian, and Megarian to the Isthmus. The sea from Antirrhium to the Isthmus is the Alcyonian part of the Crisaean Gulf. The distance from the Isthmus to Araxus is 1030 stadia. This outlines the Peloponnesus and the land across the gulf. Now, I will detail the Eleian country. |

|

| 3. The Eleian country currently includes the seaboard between the Achaeans and Messenians, extending inland to Arcadian districts such as Pholoë, Azanes, and Parrhasians. Historically, it was divided into domains ruled by the Epeians and Nestor, as described by Homer. The city of Elis did not exist in Homer's time; the inhabitants lived in villages, and the area was called Coelê Elis. After the Persian wars, many communities formed the city of Elis.

Elis borders the Achaeans to the north, ending at Sicyonia, and the Messenians to the south, near Taenarum. Notable geographical features include the Corinthian Gulf, Rhium and Antirrhium capes, and the Alpheius River, which flows through Pylian territory, not the city of Pylus.

Arcadia, located in the peninsula's interior, neighbors all these regions. Homer’s descriptions align with current conditions, emphasizing the poet's historical significance.

The Corinthian Gulf begins at Evenus River, stretching to Araxus. Its perimeter is 2,230 stadia from Evenus to Araxus, increasing if measured from the Acheloüs River. The coast is occupied by Acarnanians, Aetolians, and Phocians up to the Isthmus, known as the Alcyonian Sea.

Eleia's significant points include Cape Araxus, naval station Cyllenê, the promontory Chelonatas, and the Peneius River. Cyllenê is a small village with an Asclepius statue by Colotes. The Eleians’ gymnasium was built long after acquiring Nestor's districts, including Pisatis, Triphylia, and Cauconian territories. The name "Triphylia" comes from the three tribes: Epeians, Minyans, and Eleians.

These historical and geographical details form the backdrop of Eleia's development and its connection to the rest of Greece. |

|

| 4. Messenia borders Eleia and extends south towards the Libyan Sea. During the Trojan War, Messenia was part of Laconia and under Menelaüs's rule. The city now called Messenê, with its acropolis Ithomê, was not yet founded. After Menelaüs's death, the Neleidae ruled Messenia. Upon the return of the Heracleidae, Melanthus became king of the now autonomous Messenians. Agamemnon's promise to Achilles of seven cities, including those on the Messenian Gulf, indicates that these regions were under his control.

Messenê is bordered by Triphylia, with Cyparissia and Coryphasium located nearby. Above Coryphasium lies Mount Aegaleum. The ancient city of Messenian Pylus was situated at the foot of Aegaleum. The Athenians later rebuilt this city as a fortress against the Lacedaemonians. Nearby are the islands of Protê and Sphagia, the latter also known as Sphacteria, where the Lacedaemonians suffered a significant defeat by the Athenians.

Methonê, believed to be the Pedasus mentioned by Homer, is where Agrippa executed Bogus during the Actium War. Adjacent to Methonê is Acritas, marking the beginning of the Messenian Gulf. The Asinaean Gulf starts at Asinê and ends at Thyrides, with notable places such as Oetylus, Leuctrum, Cardamylê, Pherae, and Gerena along the way.

Significant rivers include the Pamisus, which flows through the Messenian plain, and another smaller Pamisus near Laconian Leuctrum. Messenia's landscape features cities such as Pylus, Cyparissia, and Erana. Historically, Cresphontes divided Messenia into five cities, later consolidating power in Stenyclarus. The city's strategic importance is highlighted by its acropolis, Ithomê, similar to Corinth's Acrocorinthus. |

|

| 5. After the Messenian Gulf comes the Lacon

ian Gulf, which lies between Taenarum and Maleae, curving from the south towards the east. Thyrides, a steep rock, is located in the Messenian Gulf, about 130 stadia from Taenarum. Above Thyrides lies Mount Taygetus, a lofty and steep mountain close to the sea, connecting with the Arcadian foothills. Sparta, Amyclae, and Pharis lie below Taygetus. The site of Sparta is in a hollow district, yet not marshy. Near the coast, Taenarum features a headland and a temple of Poseidon, and the mythological cavern where Heracles brought up Cerberus from Hades.

The distance across the sea from Taenarum to Phycus in Cyrenaea is 3,000 stadia, to Pachynus in Sicily is 4,000 to 4,600 stadia, and to Maleae is 670 stadia. Cythera, an island with a good harbor and city, lies 40 stadia off Onugnathus, a low-lying peninsula near Maleae.

After Taenarum, one encounters Psamathus, Asine, and Gythium, the seaport of Sparta, situated 240 stadia from the city. The Eurotas River flows between Gythium and Acraea. Helus, once a city founded by Helius, son of Perseus, is now a village in a marshy district. Following the coast, one reaches the plain called Leuce, then Cyparissia, Onugnathus, Boea, and finally Maleae. The distance from Onugnathus to Maleae is 150 stadia.

According to Ephorus, Eurysthenes and Procles, the Heracleidae, divided Laconia into six parts, founding cities, and used Las as a naval station. The surrounding peoples, initially equals, became known as Helots after being subdued by Agis, son of Eurysthenes, and forced into servitude, shaping the Spartan system of Helot-slavery. |

|

| 6. After Maleae follows the Argolic Gulf, and then the Hermionic Gulf; the former stretches to Scyllaeum, facing east and towards the Cyclades, while the latter extends to Aegina and Epidauria. The first places on the Argolic Gulf are occupied by Laconians, and the rest by the Argives. Among the Laconian places is Delium, sacred to Apollo, Minoa, a stronghold, and Epidaurus Limera, which has a good harbour. Immediately after sailing from Maleae, the Laconian coast is rugged but provides anchoring places and harbours.

The Argives have Prasiae, Temenium, where Temenus was buried, and the district through which flows the river Lerna, sharing its name with the marsh where the Hydra myth unfolds. Temenium lies twenty-six stadia from Argos; from Argos to Heraeum is forty stadia, and then to Mycenae is ten. After Temenium comes Nauplia, the Argives' naval station. Next are the caverns and labyrinths called Cyclopeian.

The Hermionic Gulf begins at the town of Asine. Then come Hermione and Troezen, and the island of Calauria, which has a circuit of 130 stadia, separated from the mainland by a strait four stadia wide. Then comes the Saronic Gulf, called a sea or strait, stretching from the Hermionic Sea and the Isthmus' sea, connecting with the Myrtoan and Cretan Seas. The Saronic Gulf includes Epidaurus and the island of Aegina off Epidaurus; then Cenchreae, the eastern naval station of the Corinthians; and Schoenus, a harbour forty-five stadia away. The distance from Maleae to Schoenus is about 1800 stadia. Near Schoenus is the "Diolcus," the narrowest part of the Isthmus, where the temple of Isthmian Poseidon is located. |

|

| 7. In antiquity, this region was under the Ionians, who were from the Athenians. Originally called Aegialeia, its people were known as Aegialeians. Later, it was called Ionia after the Ionians, similar to how Attica was named after Ion, the son of Xuthus. Hellen, the son of Deucalion, ruled between the Peneius and Asopus rivers in Phthia, passing his rule to his eldest son, while the rest sought settlements elsewhere. Dorus united the Dorians around Parnassus, and Xuthus, who married Erechtheus' daughter, founded the Tetrapolis of Attica. Achaeus fled to Lacedaemon, naming its people Achaeans, and Ion gained such repute from defeating the Thracians that the Athenians gave him governance.

Ion organized the people into four tribes and four occupational groups: farmers, artisans, sacred officers, and guards. Due to overpopulation, Athenians sent Ionians to colonize the Peloponnesus, naming it Ionia. They established twelve cities, but were later driven out by the Achaeans and returned to Athens. From there, they colonized Asia Minor, founding twelve cities in Caria and Lydia. The Achaeans, originally from Phthia but living in Lacedaemon, attacked the Ionians and took over their land.

The Achaeans, under democratic governance, became renowned for their constitutions, influencing Italiote cities after the Pythagorean uprising. After Leuctra, the Thebans used them to arbitrate city disputes. Despite Macedonian interference, the Achaeans reformed their league, starting with four cities including Patrae and Dyme, growing powerful and eventually forming a notable league. This league persisted until Philopoemen's generalship, despite Roman dominance over Greece. |

|

| 8. Arcadia, centrally located in the Peloponnesus, is predominantly mountainous. Cyllene is its highest peak, reaching a perpendicular height of fifteen to twenty stadia. Arcadia's tribes, like the Azanes and Parrhasians, are considered some of the oldest Greek tribes. Continuous wars have devastated the region, leading to the disappearance of famous cities and their tillers. Despite this, Arcadia offers excellent pastures for horses and asses.

Mantineia gained fame through Epameinondas, who defeated the Lacedaemonians there, losing his life. Today, Mantineia and other cities like Orchomenus, Heraea, and Cleitor are either non-existent or barely traceable. However, Tegea remains relatively intact, housing the temple of the Alean Athena and the temple of Zeus Lycaeus near Mount Lycaeum.

Arcadia boasts several notable mountains besides Cyllene, such as Pholoe, Lycaeum, Maenalus, and Parthenium, which extends into the Argive territory. The Alpheius, Eurotas, and Erasinus rivers exhibit unique behaviors. The Erasinus, for example, flows underground from the Stymphalian Lake to the Argive region, though it previously had no outlet due to blocked passages. Similarly, the Ladon's flow was once halted due to an earthquake-induced blockage near Pheneus.

Polybius noted that the distance from Maleae to the Ister was about ten thousand stadia. However, Artemidorus corrected this to six thousand five hundred and forty stadia, considering the specific route taken by one general. Ephorus mentions several colonizers who settled the Peloponnesus post-Heracleidae, including Aletes in Corinth, Phalces in Sicyon, Tisamenus in Achaea, Oxylus in Elis, Cresphontes in Messenê, Eurysthenes and Procles in Lacedaemon, and Temenus and Cissus in Argos. |

|

|

|

|

9 Greece. 5 103 1:25

| 1 Now that I have completed my circuit of the Peloponnesus, the next step is to traverse the peninsulas connected to it. The second peninsula includes Megaris, making Crommyon part of the Megarians, not the Corinthians. The third peninsula adds Attica, Boeotia, and parts of Phocis and the Epicnemidian Locrians to the second. According to Eudoxus, a line from the Ceraunian Mountains to Sunium divides the Peloponnesus from the continuous coastline to Megaris and Attica. He suggests that the coastline from Sunium to the Isthmus would not appear as concave if not for the districts forming the Hermionic Gulf and Actê. Similarly, the coast from the Ceraunian Mountains to the Corinthian Gulf would not appear so concave without Rhium and Antirrhium.

Peiraeus, the seaport of Athens, is located centrally on the line from Sunium to the Isthmus, about three hundred and fifty stadia from Schoenus and three hundred and thirty from Sunium. The area from Sunium northwards, bending westwards, and Actê’s eastern side towards Oropus in Boeotia is described as a peninsula with Attica and Boeotia forming an isthmus of the third peninsula.

After Crommyon, above Attica, are the Sceironian Rocks. The road from the Isthmus to Megara and Attica passes closely by these rocks, with the myth of Sceiron and Pityocamptes linked to this region. Following the Sceironian Rocks is Cape Minoa, forming the harbor at Nisaea, the naval station of the Megarians. This historical description includes the founding of Megara by the Heracleidae, displacing the Ionians. |

|

| 2 Next is Boeotia, and for clarity, I must recall my earlier remarks. The seaboard from Sunium to Thessaloniceia inclines slightly westward, with the sea on the east, and the land above it extending in ribbon-like stretches parallel to each other. The first stretch is Attica and Megaris, bordered by the seaboard from Sunium to Oropus and Boeotia on the east, the Isthmus and Alcyonian Sea on the west, and the seaboard from Sunium to the Isthmus and the mountainous country separating Attica from Boeotia. The second stretch is Boeotia, extending from the Euboean Sea to the Crisaean Gulf.

Ephorus declares Boeotia superior to neighboring countries due to its fertile soil and access to three seas with good harbors, facilitating trade with Italy, Sicily, Libya, Egypt, Cyprus, Macedonia, and the Propontis. Despite its natural advantages, Boeotian leaders historically neglected education and training, focusing solely on military virtues, which limited their success. Boeotia was once inhabited by Aones, Temmices, Leleges, Hyantes, and Phoenicians led by Cadmus, who founded Thebes. The Phoenicians' dominance continued until displaced by the Epigoni and later the Thracians and Pelasgians.

The Boeotians allied with Penthilus for the Aeolian colony, sent most of their population, and called it a Boeotian colony. Their land was ravaged by the Persian War near Plataeae but later recovered, with the Thebans defeating the Lacedaemonians and briefly dominating Greece until Epameinondas's death. Subsequent wars and Macedonian attacks led to Boeotian decline, leaving Thebes and other cities in ruins, except for Tanagra and Thespiae, which fared better. |

|

| 3 After Boeotia and Orchomenus, one comes to Phocis, which stretches north alongside Boeotia, nearly from sea to sea. Historically, Daphnus belonged to Phocis, splitting Locris into two parts. However, Phocis now no longer extends to the Euboean Sea but borders the Crisaean Gulf. Key places in Phocis include Crisa, Cirrha, Anticyra, Delphi, Cirphis, and Daulis. Parnassus, also part of Phocis, forms its western boundary.

Locris, divided by Parnassus, lies alongside Phocis. The western part, occupied by the Ozolian Locrians, extends to the Crisaean Gulf, while the eastern part ends at the Euboean Sea. The Ozolian Locrians have Hesperus engraved on their public seal. Phocis, bordered by Parnassus and inhabited by Locrians and Dorians, also lies near Aetolia and Thessaly.

Parnassus, esteemed as sacred, contains notable caves, including Corycium. Its western side is occupied by the Ozolian Locrians and some Dorians, while Phocians and most Dorians occupy the eastern side.

Delphi and Elateia are the most famous cities in Phocis. Delphi is renowned for the temple of Apollo and its oracle. Elateia, the largest city, controls passes into Phocis and Boeotia. Delphi, situated on Parnassus's western boundary, has a rocky, theatre-like setting. Cirrha, an ancient city by the sea, lies below Cirphis mountain.

Anticyra, known for its medicinal hellebore, endures, while Cirrha and Crisa were destroyed. The temple at Delphi, once exceedingly honored, now shows neglect. Historically, the seat of the oracle was a cave inspiring divine frenzy, with oracles delivered by the Pythian priestess. |

|